National Health Insurance – Finding A Workable Healthcare Model for SA

South Africa’s healthcare system has not escaped this scrutiny, and the challenges posed by the pandemic has reignited discussions around National Health Insurance (NHI).

For the first time in history a health crisis has shut down the entire global economy, painfully demonstrating how inseparable healthcare and the economy have become. South Africa’s healthcare system has not escaped this scrutiny, and the challenges posed by the pandemic has reignited discussions around National Health Insurance (NHI).

NHI update

The South African healthcare system is characterised by its two-tiered nature, in which the public and private sectors operate largely in silos. Currently, about 84% of the population rely on the public health system which is overextended, understaffed and poorly resourced. In contrast medical scheme members (making up the remaining 16%), have access to a better resourced private sector, which provides a world-class level of patient care.

South Africa’s current inequitable healthcare system continues to prevent many individuals’ adequate access to healthcare services, and clearly this needs to change. However, there are many complex issues that make implementing a universal healthcare system a mammoth task, and practical steps to move in that direction need to be examined more realistically.

What is the main aim of the NHI?

The NHI is a health financing system designed to pool risk and funds while administering healthcare services in order to achieve equality and to strengthen the under-resourced and strained public sector.

While this is a noble objective, it is not clear how this new system will address the challenges that already exist in the current public healthcare system. These include funding constraints, corruption, resource wastage and lack of management skills. Without first addressing these problems, critics often liken the NHI to being a plaster placed on a gaping wound, when in fact a complete amputation is what is actually necessary.

Resources

Government seems to believe that more funding is the main driver needed to improve outcomes, and that by effectively nationalising private health assets (which includes the R90bn currently held in reserves by medical schemes), quality healthcare for all citizens can be achieved.

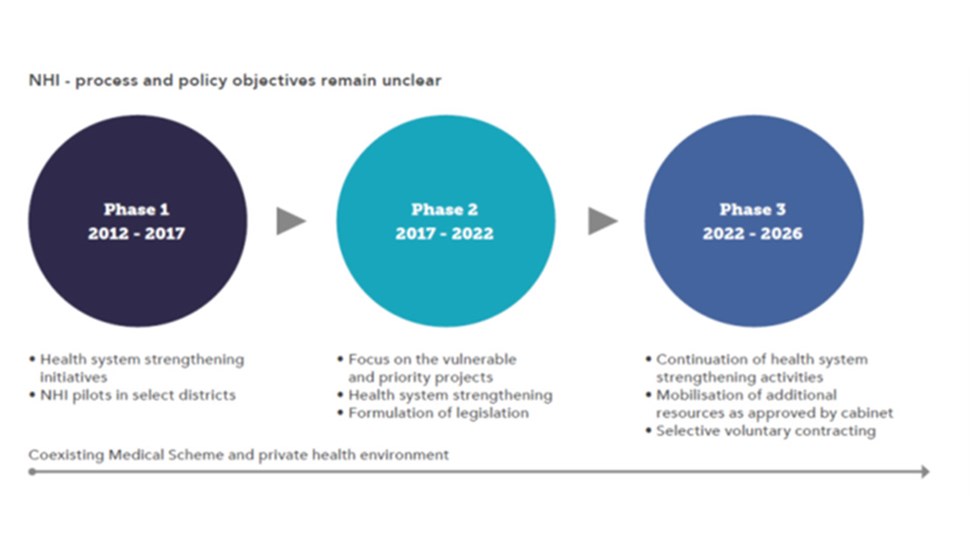

However, if we look at Phases 1 and 2 of the NHI running from 2012-2021 (see infographic 1 below), it is clear that none of the listed investments appear to have been implemented. The proposed training of nurses, upskilling of management, installation of IT systems, purchasing and maintenance of equipment, and the upkeep of buildings has not been actioned. In fact, there is a lengthy list of public hospitals in the country which are run down.

Interesting points highlighted in a report published by the Free Market Foundation (FMF) in May 2021[i] includes:

The healthcare budget may have increased, but there has been no improvement in the calibre of resources, or any outcome-based system introduced. This is clearly outlined in the research undertaken by the Actuarial Society of South Africa which revealed a number of systemic shortcomings resulting in court judgments worth millions of rands against the country’s nine provincial Health Departments. Medical malpractice liabilities have skyrocketed to more than R100 billion, with the liability provision growing at an average rate of R19 billion per annum over the past five years. If this trajectory continues for the next five years, it will almost equal the entire national health budget.

Corruption

Corruption is an ongoing problem in South Africa, and this was highlighted again recently when Health Minister, Dr Zweli Mkhize, was placed on special leave over a scandal involving the misappropriation of R90 million as part of a R150 million communication contract for NHI. There is also much anger as a result of the corruption scandals related to Covid-19 spending. All of this while the Special Investigating Unit (SIU) are already dealing with various other allegations of serious fraud and corruption in the health sector.

Concern around the NHI governance framework has remained a contentious issue, with the proposed Bill giving the Health Minister exclusive control over the appointments of the entire NHI executive, as well as the board of the Office of Health Standards Compliance[ii]. All of this is an apt reminder of the importance of an independent oversight body, as well as the need for checks-and-balances on ministerial powers.

Private sector funding all healthcare in South Africa

What is not often mentioned when addressing these challenges is that individuals on private healthcare are paying their medical scheme contributions with after-tax money. The tax they pay is what goes towards funding the public healthcare system; a system which they are not making use of themselves, but which currently funds healthcare for 84% of the country’s population. Accordingly, when including the tax paid by private companies not only does the private sector support the current Public Health System, it also removes all these individuals from the overburdened public sector, reducing the responsibility and cost on the public sector.

How will this impact those on private healthcare?

Section 27(1)(a) of the Constitution states that everyone has the right to have access to healthcare services, so how will these changes affect those who currently have access to private healthcare?

A recent presentation by Professor Nemutandani of the Health Professions Council of SA’s (HPCSA)[iii] before the Health Portfolio Committee, called for the confiscation of R90 billion in medical scheme assets, stating that these reserves will be better used under government control. As pointed out in a recent Financial Mail article, this was a remarkable statement coming from a statutory body set up to regulate medical professionals and protect the public. Critics have argued that these statements are driven by ruinous ideology rather than common sense, and that they don’t contribute to inclusive and constructive discussions on how best to achieve a universal health system.

It’s clear that the debate about transforming healthcare services can’t be conducted in the abstract, as too much depends on it. There is fair consensus among academic and legal experts that the independence of the judiciary, which has proven to be resilient under trying conditions, will prevail and resist the short-term expediency of politicians.

Of the R90 billion currently held collectively in reserves by medical schemes, legislation prescribes that medical schemes must hold at least 25% of their annual contributions to cover unforeseen emergencies. However, these are private assets belonging to medical schemes and their respective members and it cannot be “nationalised” and paid across to the NHI to fund it.

Ultimately, the form that medical schemes will take in future still requires much research and debate, and there is a wide range of roles that the private sector could play which would harness the capacity and enhance available expertise.

Workable alternatives

At a recent event hosted by the health policy unit of the FMF it was concluded that NHI was unaffordable, legally ill-considered, and would not achieve its stated aims.

The general belief among several commentators was that there are various reforms that can be considered without insisting on adopting NHI as the only alternative. Themes of these reforms revolve around encouraging competition, deregulating the industry, and eliminating political interference. Medical aids agree that efficient ways need to be found to support a larger proportion of the population, but Professor Nemutandani’s approach – seizing medical aid reserves – isn’t the answer. Ryan Noach, CEO of Discovery Health, accepts that the medical aid industry needs “structural reform” but emphasises that the trick is to do this in such a way that it does not destroy existing assets.

In recognising the willingness of the private sector to engage and improve healthcare for all, there is an opportunity for government to harness the strengths and capacity of this sector in delivering quality services, managing benefits and pooling funds. Collaboration is key if the intended broader vision is to be realised, even if it means proceeding at a gradual pace over a longer period.

References

[i] The FMF is an independent public benefit organisation founded in 1975 to promote and foster an open society, the rule of law, personal liberty, and economic and press freedom as fundamental components of its advocacy of human rights and democracy based on classical liberal principles.

[ii] The Office of Health Standards Compliance board, will be the statutory body that will undertake provider accreditation as to who will get contracts with the NHI fund.

[iii] The HPCSA is a statutory body, with senior appointments made primarily by the minister of health. The same minister who will exclusively appoint the entire board and executives of the proposed NHI Fund as well as the board of the Office of Health Standards Compliance – the statutory body that will provide accreditation as to who will get contracts with the NHI fund.