South Africans have had a love-hate relationship with Trusts for the longest time. We love the protection it provides against the wrath of a spouse, the greed of SARS and the persecution of creditors. But we hate the costs and admin associated with it, the loss of control and erosion of the tax benefits we enjoyed in the recent past.

Professionals differ in their approach to its uses and benefits, and to get contradicting professional opinions is the rule rather than the exception. Accounting professionals point out the two dimensional short term tax expense of trusts, the financial advisory profession often point out the higher capital gains tax rate and the FICA burden a trust creates, whilst estate planners sing the praises of the unique legal nature of a trust which can carry wealth across generations so seamlessly.

To compound the complexity, trusts are used across multiple jurisdictions and as ownership vehicles for assets situated in many countries. Each country also taxes proceeds from trusts differently.

Each voice in this debate carries with it an element of truth, and element of half-truth and an element of exaggeration. Somewhere in between is a bespoke truth relevant to each individual estate planning scenario. Absolute viewpoints tend to do more harm than good.

What we do know with certainty is what trusts are and how trusts differ in principle.

A trust is an arrangement between a person who gives something to someone to own on behalf of a group of people or for a specific cause. In South Africa we explain this transaction in contractual terms and our trusts are also of contractual nature, or the product of a will. We recognise a founder who donates or bequeaths something to trustees to hold on behalf of beneficiaries or a cause. We use the law of contract and the law of testation, coupled with several unique principles to understand a trust.

Many offshore countries like Guernsey, Jersey, and Isle of Man (the so-called offshore jurisdictions) have a more pliable legal understanding of trusts. For them for instance a trust can just be declared to exist by a trustee. In all these examples however, there is a relationship of trust where trustees care for beneficiaries with funds entrusted to them.

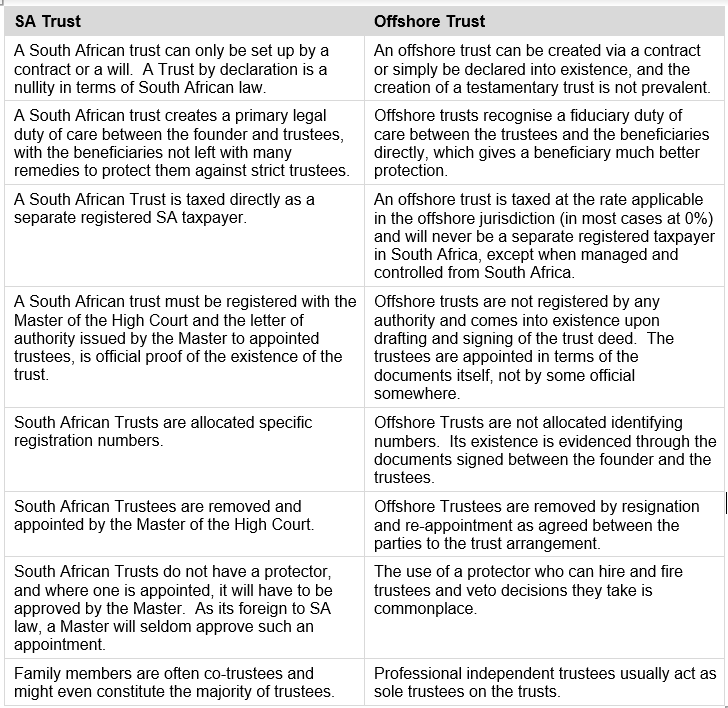

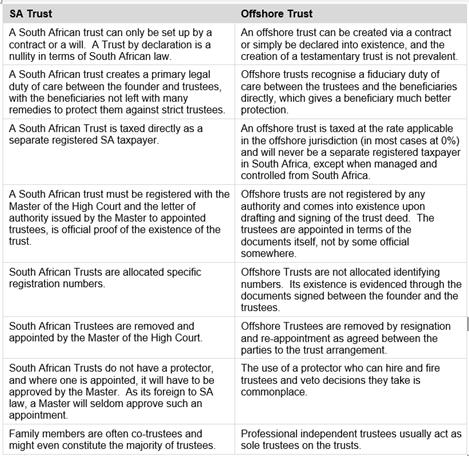

The main differences between South African and the typical “Offshore” can be tabulated as follows:

The one similarity between the local trust and offshore trust is the taxation thereof with one very important difference: The local trust is a SA taxpayer and the offshore trust is not. Why is that so important? Well the reason is that the tax consequences that follows the establishment of trusts largely depends on choices that is made by the founder and the trustees.

Both local trusts as well as offshore trust are subject to both attribution rules and the conduit principles of trust taxation. Whether either of the rules are triggered by a founder who funds the trust or a beneficiary who receives benefits from the trust, is determined by choices made.

The attribution rules apply to any gratuitous transaction between a founder and the trustees. Gains are generally taxed in the hands of the founder to the extent that the gain was made because of and to the extent of the gratuitous transaction. If a founder for instance donates an asset to a trust and the trust sells that asset for a profit, the trust would not have made the profit had it not been for the initial donation of the asset.

For a local trust, the rate of taxation in the trust is higher than that the rate of taxation on the gain for the individual. Therefore, the attribution rules would be a beneficial choice to make. An offshore trust situated in an offshore jurisdiction is taxed at 0%. Attribution would therefore not be the greatest tax planning idea. The structuring needs to ensure that the transaction is not gratuitous by nature.

The same applies for the conduit principle, where it is recognised that a trust is sometimes just a vehicle through which gains and income is channelled to beneficiaries. Again this might make sense in the short term where the trust and beneficiaries are in South Africa, as the beneficiaries will have a lower rate of taxation in general to that of the trust, but it might not make sense with regards to an offshore trusts where the trust is taxed at 0%.

For both local and offshore trusts, the gratuitous nature of an interest free loan is deemed to be a donation of the interest forgone and donations tax is levied on this if the aggregate of the interest would have been more than R100 000 per person per year. Due to the need to transact on an arms-length basis with an offshore trust, the deemed donations tax is usually not applicable to the funding of the offshore trust (these rules are colloquially referred to as the section 7C rules).

Local trusts tend to be managed and controlled by a family group with the inclusion of at least one independent trustee. Most of the actual work done on many trusts would therefore be done between the family and the accounting firm looking after the accounting and tax compliance. To date, the “clampdown” on trusts where the separation between individual and trust have not been properly structured. has not happened. Never say never, but this also means that currently the cost of a local trust seems to be a lot lower than that required to manage an offshore trust.

To ensure that an offshore trust is not deemed to be a South African controlled entity which would give SARS taxing powers over the offshore trust, almost all offshore trusts are managed exclusively by an offshore professional corporate trustee. This means that the offshore trustee is solely responsible for the management of the trust assets and the accounting for the work done and decisions made, which increases the professional fees payable. Most offshore trustees would charge a set-up fee or a take-over fee as well as an annual management fee which includes the basic accounting work that is required.

Whichever way one look at trusts, whether it is local trusts or offshore trust, the benefits of trusts are directly related to the quality of the trustees, their knowledge of the law in which the trust operate, their administrative ability and competence and above all, their trustworthiness and ethical standards.

Trusts function within a legal scale of grey (as opposed to the black and white environment of the accounting world), which makes it a complicated vehicle to use. Bad things happen in trusts through ignorance of the law, or the level of ethics and skills required by trustees.

It is advisable to obtain legal assistance to navigate the complexity of a trust to achieve the simplicity in estate planning that lies on the other side of it.